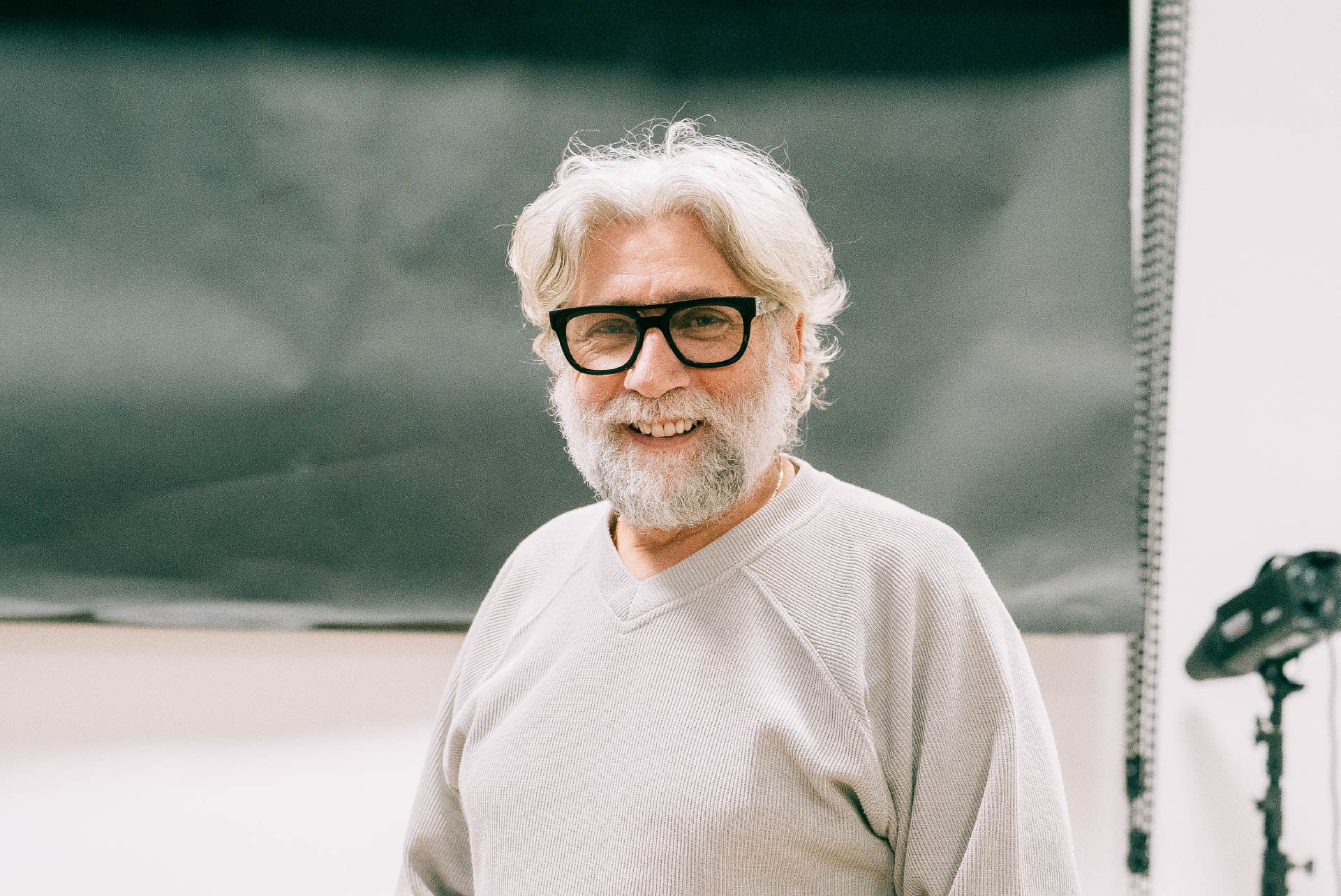

Political scientist Jozef Lenč: Instead of civic education, we are pushing mathematics. Maybe that is why our civil society is so weak

People often have the feeling that politics only affects parliament or the government. However, it is present everywhere – at the university, in local government, in their everyday decisions. It is just a matter of starting to perceive it that way, says political scientist and university teacher Jozef Lenč.

I read that you studied mechanical engineering at a secondary technical school. How does a mechanical engineer become a political scientist? That is a relatively big study shift from a technical trade to social sciences.

In my case, it was probably the result of rebellion and utopian ideas about what I wanted to do in life. I went through elementary school with only the best of the best, and everyone told me that I should go to grammar school, where I would finally have to start really learning. So I said that I wanted to go to a mining school. In the end, I ended up at a technical school, which was a kind of compromise between a vocational school and a grammar school. For some reason, I was also fascinated by maritime transport at the time, I wanted to be a sailor, although I had absolutely no predispositions for this type of technical field.

At that time, in the early 1990s, it was also said that from a mechanical engineering school, you couldn't go anywhere else except to a technical university. Despite this, I was eventually accepted to study political science.

Was that something you had dreamed of while you were studying at the industrial college?

At the end of high school, I had more of an idea of going abroad. I was no longer interested in shipping, but I wanted something that would take me further. However, I wanted my parents, especially my mother, to have peace of mind. I told them that I would apply to two universities and that if they accepted me, I would still stay in Slovakia.

One was for law in Banská Bystrica, where I had not actually prepared for anything, and that is how it turned out (laughs). The other was for political science at the University of Trnava.

You have already been accepted to that one.

Yes, because I have been interested in politics since childhood. I remember that before 1989, I regularly watched the evening television news with my parents. Not to mention the events after November 1989. My father, although he did not have a university degree, always read three dailies – Pravda, SME and always some tabloid media. I once asked him why he did it. He told me that he wanted to read different views on politics and then form his own opinion from them.

And that is exactly what shaped me. Reading newspapers every day helped me to orient myself in politics and probably thanks to a good general overview I managed to successfully pass the admissions exams.

You completed your master's degree in political science at the University of Trnava. Doctoral studies at the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Why not at the Trnava University?

At that time, the University of Trnava did not have accreditation for doctoral studies. For this reason, shortly after arriving at UCM, I started external doctoral studies at the Institute of Political Science of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, which had a doctoral program associated with Comenius University in Bratislava.

You have been working at UCM as a teacher and scientist since 2003. Do you still remember your arrival?

This was also an interesting chapter in my life. I had started at UCM even before that, in September 2002 for civilian military service. So for a year, a month and 15 days, I defended UCM from external enemies as a "soldier" (laughs). When my civilian service ended, I received an offer to stay here as an assistant professor.

What appealed to you most about the academic environment at UCM? Or in other words, what is it that has kept you at the university all these years?

Loyalty in particular. I had other offers as well. For example, around 2005, the army approached me to lecture to soldiers who were about to go to Afghanistan. The topic was Islam and the politics of Islamic states. It was a one-time training, but after it a certain gentleman approached me and asked if I would like to work for them in this field long-term.

Given that I completed my civilian service at UCM, it seemed a bit strange to return to work in the army. So I stayed. Maybe it's also a part of my inner conservatism, but mainly loyalty to the place where I started. Since then, I have worked first at the Department of Political Science, and now at the Department of Philosophy and Applied Philosophy.

At the aforementioned Department of Philosophy and Applied Philosophy of the Faculty of Arts of UCM, you provide, among other things, profile subjects of the study program Teaching Citizenship Education. I don't want to generalize, but what knowledge do high school students come with in this area?

This depends on several factors. What school the student comes from, what kind of civics teacher they had, and, of course, the overall knowledge of the particular person.

If a student comes from a grammar school where he had a good teacher and high-quality civics teaching, his awareness is usually significantly better. On the contrary, students from secondary vocational schools often only have a civics card in the first year, if at all, and this is also reflected in their knowledge. In some places, civics is still perceived only as a filler lesson. Something that can be replaced by another lesson if you need to catch up on mathematics or Slovak. In such a case, it is clear that students come with very weak foundations.

In general, however, I cannot say that the best of the best come to us from secondary schools.

So where are they?

I think we both know the answer to this question - abroad. A few years ago, a student organization that brings together selective secondary school students approached me to mentor a simulated election project in which students from across Slovakia participated. The students were excellent, but when I asked them where they wanted to study, they mentioned the Czech Republic and countries further west. Slovakia did not figure among their future study options.

Just a quick note on the neglect of civics. We can probably agree that understanding the functioning of the state, its processes, and the European Union is one of the key tools for the healthy development of democracy.

Of course, that is only one part of what civics should cover. It is a subject that should prepare young people for life in our society. So that they understand the political system, know how to protect it, know their rights and freedoms, they should also learn economic, legal, and media literacy. Thanks to it, they should become full-fledged citizens who can integrate into society after school.

We have it all on paper, but in reality, civics education is very weak. People learn many things as they go through life, and often from their own mistakes. It doesn't matter whether someone goes to high school or vocational school - everyone becomes a citizen, but some are not ready for it.

But instead of civic education, we are pushing for mathematics, which will be a mandatory high school subject, or physical education, which was hotly debated in parliament in the context of adding a third lesson a week. I don't want to discredit mathematics, but its advanced secondary school level will only be really used by those who go to university to study technical or natural science subjects. An ordinary person will not use sines, cosines or tangents in their lives. Maybe that's why our civil society is so weak - we lack legal, economic and media literacy.

What else needs to change in education so that we can educate critically thinking generations who will actively participate in the development of democracy?

Civic education should not only be strengthened, but its content should also be fundamentally revised. I am talking primarily about dividing it into meaningful thematic units. At the same time, its teaching should be better timed to the age when the topics are relevant and sufficiently understandable for the students. I do not think it makes sense to teach it from the fifth grade. It would be much more meaningful to focus on secondary schools, where students are already criminally responsible, for example, and should know what obligations this entails.

It is at that time that they should learn about their rights, responsibilities, but also about how society works, the importance of relationships, laws, the constitution, children's rights and basic human rights. So that they know that they are not

Do you feel that current students are more interested in politics than the generations before them, or vice versa?

I am already at an age where I naturally fall into the group of people who repeat the old, well-known phrase: “It was better for us.” Although the turnout of first-time voters in elections has not changed fundamentally, I really think that at least we, political science students, have been more engaged. In 1998, for example, we participated in a volunteer campaign before the key parliamentary elections, where we convinced people all over Slovakia to go vote. In 1999, we devoted ourselves to raising awareness about the needs of people with disabilities, and in 2001 we ran a student campaign for Slovakia’s accession to NATO. Politics was simply a part of our lives and studies.

Today, disinterest prevails. I also see this at the meetings of the academic senate. Not only from the students, but also from academics and employees. Often, only one or two people from the public come to them. There are very few candidates running for office. Students are a little more active now, as they have their own representatives, but it is still significantly weaker than it was ten or fifteen years ago.

How do you specifically try to motivate your students to not perceive politics as something distant, but as part of their lives?

I try to talk to them. Encourage them not to be afraid to ask questions about anything that interests them. At the beginning of their studies, they are often passive, but after four or five semesters we can openly discuss many things. I also try to explain to them that politics is not something distant, but that it concerns them fundamentally. And it doesn't matter whether they are interested in it or not. They are part of politics and politics is part of their lives.

People often have the feeling that politics only affects parliament or the government. However, it is present everywhere - also at the university, in local government, in their everyday decisions. It's just a matter of starting to perceive it that way.

You regularly comment on current political events in the public sphere. Was this an intended part of your professional career as a political scientist from the beginning or did it come about by chance?

It was more of a coincidence. Around 2010, one of our students worked at TA3 and wrote her diploma thesis with me. When they were looking for someone to comment on political topics, she recommended me. This is how it often works in the media. On their part, it is usually not a systematic search for experts, but they choose the easier way and turn to someone with whom a particular journalist has contact and who can respond quickly, clearly and concisely.

In this regard, my teacher Michal Horský helped me a lot, who taught me not only political science, but also how to appear in the media. He gave me two key pieces of advice that I still follow to this day. The first was to speak clearly, briefly and with a punchline at the end. The second was not to impose my opinion on anyone. The role of a political scientist is to ensure that people do not know who they are voting for. It is essential to evaluate how the system works and whether political actors act within its rules. If a political scientist wants to express his or her opinions, he or she can write comments.

Is it possible to teach political science today without commenting on current political events?

Of course. Most political science teachers do not comment publicly on political events, and this does not at all call into question their professional or academic qualifications. Some simply prefer to write, do research or lecture. Sometimes this may be due to fear of public reaction, lack of experience with media communication or institutional restrictions. However, none of this means that they are not sufficient experts in their field.

I spoke with several leading scientists from UCM, and some of them stated that one of the key problems of Slovak higher education is its closed nature. Why is this? Are we not confident enough or comfortable entering into public debate?

It's not just about whether we want to, but also whether we can. Wanting means seeing the point in it and having personal predispositions. Being able means having time, approval from your immediate family, but also the certainty that your public appearance will not threaten your existence – for example, by losing your job or income, which is the reality today for many who have mortgages or other obligations.

Luck also plays a big role. Someone has to reach out to you or at least be willing to provide you with space. There are many reasons why the academic world is often closed in our country, although I clearly think that it should be more open.

I will just add why I am asking this question. We live in a post-factual era, the hallmark of which is distrust in scientific and educational institutions in general. However, isn't it crucial to the fight against disinformation and populism that the voice of scientific and educational institutions be heard as much as possible in the public space?

Of course. When only populists and disinformation are heard in society, their voice will soon become dominant. After all, we have been seeing this in the media space for several years now. Therefore, the question is whether this should not have started happening much earlier. Haven't we been silent for a dangerously long time?